Writing Out Loud: Sample Chapter

Chapter 3: Eyebrows Up

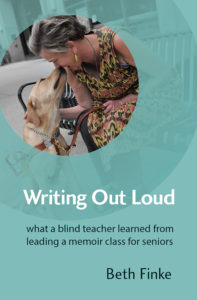

From Writing Out Loud: What a Blind Teacher Learned from Leading a Memoir Class for Seniors

From Writing Out Loud: What a Blind Teacher Learned from Leading a Memoir Class for Seniors

“Hello?” No answer.

The classroom is empty when Hanni and I arrive. High ceilings echo our movement, making the room feel bigger than it is. But Hanni and I have practiced this. We thread our way to a seat at the table. I fish my memoir, Long Time, No See, out of my backpack and plunk it on the table. With any luck, it has landed face up. A published book might lend me some credibility with these senior citizens.

I poke the button on my talking watch. “It’s one-seventeen-p-m.” Class begins at 1:30. I should have brought Braille to read. Books on tape don’t work at times like this – headphones prevent me from hearing what’s going on around me. I need to be aware if, by some miracle, a senior shows up.

A copy machine whirrs in a nearby office. Footsteps tread past my room. Time trickles. No, it’s more annoying than that. It drips, like water from a broken faucet.

The vacant room comes as no surprise. Who would sign up for a writing class taught by someone who didn’t know how to teach?

I press my watch again. “It’s one-twenty-three-p-m.” Still just me and Hanni. I bend down to pet her, and just as I place my hand behind my head to avoid bumping it on the way up, the miracle happens. Seniors start showing up for class. All at once. At first I’m startled by their arrival. Then I’m surprised at how happy I feel. Apparently they actually believed the stuff they read on those posters.

“My name is Beth,” I say, as chairs shuffle around. Have they noticed the dog under the table? Do they know I can’t see them? I don’t know.

“Is this the writing class?” one of them asks. I sense skepticism.

My sister Marilee learned at a teaching seminar that if you talk with your eyebrows up you sound more positive. I decide to give eyebrows-up a try. Throwing out a laugh, I say, “This is it! This is the writing class!”

Eyebrows-up works. The students stay.

I ask them to introduce themselves. They have great names. Minerva. Lita. Ida. Hannelore. Tom is the only man, and he has brought his wife along. Why? I don’t ask. I’m just glad they are all here.

By asking them to tell me a little bit about themselves, I learn that these senior citizens have grown up on the South Side, in the suburbs, in St. Louis. One has a Master’s degree. Another never finished high school. A third completed her

Associate’s degree at age 72. When Louise introduces herself, I have a little trouble understanding her. The puzzled look on my face forces her to explain.

“My tooth ith mything,” she says. She hadn’t been able to get an appointment with a dentist before today, and she didn’t want to miss the first class.

“Ooooh. Does it hurt?” I ask.

“No, it juth lookth terrible!” she says, all her sibilant sounds lingering longer than they should. “I’m holding a Kleenecth in front of my mouth while I talk,” she explains. I remind her that I won’t even notice how she looks. “I’m sure no one else here will mind, either.” The class reassures her they won’t. Louise puts the Kleenex back in her purse.

A retired postal worker, Louise had gone to college in her 60s and studied theater. “I want to be an actreth!” she announces. We would soon learn that Louise does indeed have a sense for the dramatic.

Missing teeth aside, one thing all of the students have in common? They are all writers. Some have taken other writing classes. One woman retired from a career in journalism and PR, for Pete’s sake.

Act professional, I tell myself. Don’t let on. But I know I’m sunk. I thought I had one – and only one – chance of getting away with this sham: the students all had to be naïve beginners. But not this group.

Deep breath. Eyebrows up again.

My plan for our first meeting is to show them how to dictate their memories into a tape recorder. The method had worked for me when I recorded the rough draft of my own memoir from a hospital bed years ago, when I’d spent months after my 26th birthday undergoing surgeries in a vain attempt to save my eyesight. A hospital social worker suggested I record an audio journal, which I later transcribed with my talking computer. Those tapes eventually led to Long Time, No See. So I knew it could work for my seniors.

I’d brought special five-minute-per-side tapes for them. “All you have to do is go home, sit down with a recorder, and talk about what it was like getting to school in the winter. What did you wear? How long was the walk? Who did you walk with? Where was the school?

“Let yourself go off on tangents at first,” I say. “What do you think of when you remember those cold days? Long underwear? Mittens? The smell of your wet socks drying on the radiator?” If the tape runs out, I tell them they should turn it around and start over again. “Keep doing this until you finally get it down to five minutes,” I say, pointing out that one easy way to accomplish this would be to devote the entire essay to one specific thing. “You’ll be amazed what all can be said about long underwear.”

I have it all worked out. My writers will bring their tapes back to the next class. I’ll take the cassettes home, type up what I hear, bring the papers back, and hand them out. “Look! You all wrote something!” I’ll say.

I finish telling them about my great idea, and the room falls quiet. They are riveted, I’m sure, by the thought of recording their stories.

But I’m wrong. They are simply being polite. The silence stretches between us, and then, suddenly, they erupt in protest. “Our other writing teacher told us never to use cassette tapes. He said we should only write!”

I surrender. “Forget the tapes. Don’t talk about your walks to school,” I tell them. “Write about them instead.”

They fiddle with bags and briefcases. Nothing has been said about class being over, but everyone is ready to leave. I’m about to stand up and give Hanni the “outside!” command when I feel a gentle tap on my wrist.

“It’s Minerva,” she says. “I’ll take one of those cassettes.” I want to reach out and hug her, but in an attempt to maintain my professional image, I reach for my backpack instead. Digging through my stuff, I find a tape and hand it in her direction.

“Do you need a recorder, too?” I ask, willing to lend mine to this woman with the sweet, dignified voice.

“No thank you,” she says, unzipping her handbag and sliding the cassette inside. “I have one.”