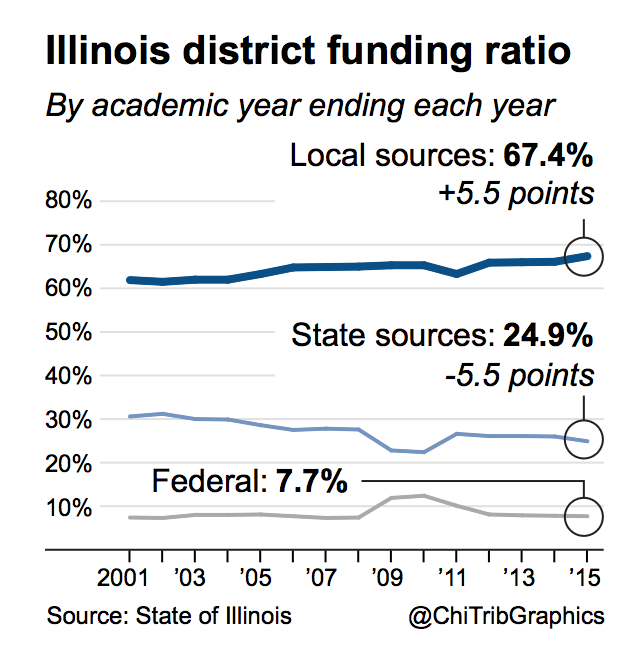

A couple of stories caught my eye this past week. One is from the Chicago Tribune on Illinois’ system for funding schools. The way we fund schools in Illinois is nothing new, and it keeps not changing thanks to dysfunctional politics, but the short of it is that Illinois relies to an unusual degree on local property taxes to fund schools. One result is that affluent districts—the ones with enough money to also pay for test prep courses and other aids—are willing to pay out the nose for good schools. For those who think there’s a crisis in public education, it isn’t in these places.

But its residents pay out the nose.

And it gives poor areas short shrift—even with Federal programs designed to attempt to balance the deficit poor localities face when it comes to education compared to rich areas. Anyway, it’s a long piece, but if you’re an Illinoisan, or you just care about education, it’s worth the read.

The other story was about how selective enrollment schools haven’t had the positive impact hoped for when it comes to kids from lower income areas who get in. In fact, the story explains how attending the likes of the vaunted Walter Payton High School actually hurts their chances of getting into elite colleges.

Education is always in the news. Charter schools are always a controversial topic, and they’re going to be even more so in the near future. In my view, selective enrollment schools and charter schools are flip sides of the same coin. They represent an abandonment of the very principle of public education; they are gimmicks to subvert public education, and they run from root problems.

Here in Chicago, you may have heard we have a gun violence problem. In my view, we have a neighborhood poverty problem that has worsened in my lifetime. And, in my view, a big cause has been collective loss of interest in the notion of common interest, of shared interest—public interest—as manifested by our support for public education.

When I grew up (here comes the get off my lawn part), schools were a part of the fabric of our neighborhoods and of our community life. That they were healthy made a big difference.

What we have in Chicago, as best I can tell, is a system that siphons many of the best students—the kind that can help anchor a healthy school culture—out of their neighborhood schools.

I’m no Ph.D., but that would seem to make it harder to maintain a healthy school culture, and easier to hollow those schools out, write those schools off and eventually close them.

And the neighborhoods suffer for all that; it’s a slow painful bleed. And I don’t think anything’s going to get better until we recognize our common interest in making sure kids on the South and West sides get a good education—in their own backyards.

You are absolutely correct. I wish we could go back to the way it was, not that it was great before. This is just a different kind of segregation.

You are so right, Mike. Efforts to change the funding system have worked in a few states, but not in Illinois. There are some things citizens can do to help, however. I belong to an organization of women that has adopted an uptown school – high poverty rate, mostly immigrant children. We hold an annual fund raiser for the school. Last year we bought instruments for the band, this year we got smart boards for teachers. We volunteer in classroom, and twice a year we buy a book for each student. So I recommend connecting with your local school and finding out where their needs are. CPS also has an office to channel volunteers.

As for selective enrollment, I am torn. Each child should have the opportunity for a good education while in school; we shouldn’t deny that for a principle that would provide good schools to a future generation of children. Granted that charter schools aren’t necessarily better than local schools. But as a mother, I would want my child in the best school available, charter, selective or otherwise. In Germany, there are no neighborhood schools past 4th grade, parents choose schools for their children. There is some segregation by academic ability and social class, but there is choice for everyone. This approach was tried successfully in one New York City school district (District 2), where all public schools became schools of choice, with schools choosing different areas of focus (science, art, music etc.). It took one crazy dedicated superintendent to do this, and I don’t know if it outlasted him. I like that approach, but haven’t seen it advocated anywhere.

Principals make an incredible difference in schools; I have seen miraculous turn-arounds in schools with a change in principals. There are organizations that work with principals, and here may be another opportunities for donating your hard-earned money.

Thanks Brigitte. I don’t disagree with any of this. And I applaud your efforts with the school, while despairing that it is necessary.I feel that the root problem is neglect of local schools (and moreover, entire neighborhoods), and that the “solutions” actually makes that problem worse. I don’t put much stock in vouchers, either. I don’t think market-based ideas are solutions. I don’t think gimmicks can substitute for a commitment, a full commitment, to public education.

Keep writing, Mike.

. Sent from my iPad

>

hear! hear!

Mike, you have laid out a very profound script for what ails our schools. I no longer have to worry about that since my children are grown, but when my son, living in the South Loop, was supposed to go to Phillips HS, I rebelled and couldn’t imagine how screwed up the public schools were. Poverty is the curse of the system. Those who live in privileged environments don’t understand the nightmares of education suffered in impoverished communities. Are we any closer to an answer on how to fix this? I don’t think so. For those fortunate enough to get into good schools, bravo. But, for those who are not, public schools do not offer the answers. Like you and others who have commented here, I am torn on this subject. But every child deserves an equal education. When we segregate the best minds from the average minds, we undermine the potential of all kids. Still, I cannot help myself: charter, professional and specialty schools, no matter how great they are, only rob the underprivileged of seeing what is possible beyond a life of misery, poverty and isolation.

Mel, I know a lot of people like you who are committed to public schools but that at a given point in time, they just felt like they had no choice but to withdraw. I didn’t face that in our circumstances, but I certainly can empathize.

I know that charters and selective enrollment schools are touted by their champions as tickets out of poverty for some kids. And I’ve tried to keep an open mind about charters, but the evidence for them is scant and when I do find it, it’s not solid. And then, here in Chicago, they just provided another avenue for corruption. There may be a place for them in some scenarios, but I would look at them as a last, not a first, resort. In my ideal world, we’d have a total commitment to public schools, in all neighborhoods, and in the worst neighborhoods in terms of poverty and crime, we make those school oases for the kids down there–as well as central community centers to provide as much as possible of what they wouldn’t otherwise get. Education is central to reversing the fates of those places, it makes sense that schools would physically and intellectually be central, too.

Thanks for the thoughtful comments, Mel, as always.

I wholeheartedly agree with your thoughts, Mike. I am particularly opposed to charter schools, which take public funds away from existing public schools. Better to use those funds for initiatives that might improve the learning environment, both in and out of school, for impoverished students. Even in so-called lottery charter schools, parents have to have the time and wherewithal to fill out paper work and even apply for their kids to have a chance to get in. Charter schools have less oversight, and studies have shown that very few statistically perform better than their counterpart public schools. Until we address the endemic poverty of these children’s lives, the schools will be unable to educate them adequately to becoming vital, contributing members of their communities and society as a whole.

What you said, Mary. All of it.

Mike–I haven’t had the time to write a full response, and this won’t be complete either but I wanted to chime in. You raise many excellent points, but we all need to be careful about how we categorize schools. Here in Evanston we have “plenty” of money for our schools, thanks to extraordinarily high property taxes (at the risk of antagonizing all Chicagoans, even with your recent increase you don’t come close to what we pay here), which fund about 80% of our budget at the high school. But we also have a low income student population of around 45% and we have a majority students of color (Black/African American 30%, Hispanic/Latino 18%, White 44%, Asian 5%, 2 or more races 2%). I think the evidence-based model of school funding reform that is being floated around (starting with ED-RED, a suburban Cook County advocacy group of which Evanston is a member) is a good approach, but it contemplates a lot more money in the system that would go to the schools most in need, like many in Chicago. It would not take money away from districts like Evanston’s who I would argue should not be penalized for our local support and our sucessful results. See here for more on our high school:http://www.eths.k12.il.us/domain/220. Because Illinois is last among all states in state dollars that go towards schools, this should be a reasonable idea, but given the state of our state, it doesn’t have legs at the moment.

Thanks for the response and for all the work you’ve done on the board. I’m with you–its not simply a matter of “New Trier has too much and Phillips not enough.” And I know about the property taxes–YIKES. Plus, rural school districts have their own issues. I’ll read about the ED-RED proposal when I can give it time. Seems like generally, more state aid and less reliance on property taxes would be a good start. But as you say, the state of the State ain’t so great.

Leave a Response