Two of the “What My Parents Believed” essays read out loud at our Printers Row memoir class last week seemed perfect for a Fourth of July post, and writers Robert and Maggy generously agreed to let me share excerpts from each of their essays here. Three cheers for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

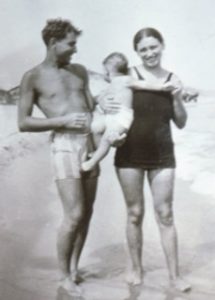

A disinterested Robert and his parents, Morris and Dorothy, on the dunes of Lake Michigan.

Robert’s essay opened by introducing his grandfathers. Both were named David. One was from a family of woodcarvers In Odessa, the other from a family of tailors and weavers in Kiev. ”Both Davids believed the legends of streets paved with gold in America,” Robert wrote. “And both risked what little they had to embark on a tortuous one-way ‘third class’ journey by land and sea to the land of freedom and opportunity.”

Each David arrived in Chicago around 1905, only to discover the pavement here isn’t made of gold after all. “In fact, the roads were covered with horse droppings about the same color as the cart tracks back home.” Hart, Schaffner and Marks hired David the tailor from Kiev to sew pockets into overcoats. David the woodturner from Odessa started selling furniture from a horse-drawn cart, then opened a furniture store on Chicago’s South Side.

Another class member, Maggy, opened her essay describing her parents’ families as solid members of Haiti’s middle class – teachers, lawyers, shopkeepers. “In Haitian society back then, your last name immediately signaled your history, your social status, and, for many people, your destiny.”

After becoming exiles in the United States, it was difficult for her parents to give up their belief in a social order that determined one’s standing in life. “Back in Haiti, only well-educated people could earn good money and respect from others in society. They shook their heads to think that our unlettered neighbors in America –the cook next door and the truck driver down the street – were making a decent living.”

Maggy’s mother eventually came to appreciate living in a society free from many of the restrictions that Haitian society applied to people, especially women. “Despite the high cost of living and the cold weather, she loved the freedom to create her own life, to meet different people, and to give her children a future that was unavailable back home.”

Robert’s parents met in Chicago in the 1920s, and, as he puts it, “the Great Depression greeted my arrival.” As the American economy recovered, Grandfather David (the one with the furniture store) bought the newly built 100 room Paradise Arms Hotel on Chicago’s Washington Boulevard. “The property prospered, but in the financial turmoil of 1932, two unfortunate men turned gunmen walked into the hotel, demanded all the money, and then killed him.”

One of Bob’s uncles eventually took over the hotel, and the family stayed involved in real estate. “My parents believed in the American dream. He would work hard in construction. She would work too. Their children would go to college.”

Maggy’s father had been a lawyer in Haiti, but since his training had been based on French civil code law, he couldn’t practice in the United States. After settling in New York City, he became a bookkeeper. Her mother was a schoolteacher in Haiti. She found work in factories and eventually learned enough English to become an X-Ray technician.

“Like most immigrants, my parents believed in hard work, and adapted to the twists life threw at them,” Maggy wrote. Robert agreed. “As the depression wound down, my dad started a remodeling business and then added a lumber yard that he ran for 35 years…the streets brightened with a golden glow.”

As for Maggy’s father in New York City, having escaped the brutal Duvalier dictatorship, he admired the American system of democracy. “Every 4th of July he would read the Declaration of Independence printed in the New York Times, and make us kids read it too,” Maggie wrote. “My parents believed that America was the greatest country on earth.”

Above all, Maggy’s father believed in his daughter when it really mattered. Maggy was 25 years old and working in advertising when she decided to sublet a co-worker’s Manhattan apartment. “As expected, my mother forbade me to move out of the house,” Maggy wrote. “No respectable unmarried woman lived by herself. What did I want to do by myself that I couldn’t do at home?”

As her mother carried on, Maggy climbed the stairs to see her father in his attic office. Isolated from the din below, her father patiently listened as she explained between tears. “I wasn’t rejecting the family. I did not intend to bring shame and dishonor upon them,” she wrote. “He understood, and gave me his blessing to spread my wings and fly.”

What a lovely read. Wonderful memories of people who strived to make a better life for themselves without expecting society to do it for them.

I love this one. Regarding streets paved with gold, when I was in the Gambia a couple of years ago, I was told by one of the villagers there that I certainly was not blind, because there are no blind people in America.

Now that’s a new one on me! If only it were true…

Thank you. Both stories are the stories of all of us in this country. They made me appreciate my brave grandparents.

Yes. When you look into history, it’s kind of miraculous any of us are here — so many of our ancestors endured unthinkable hardship. Big thanks to Robert and Maggy for their willingness to let me share their stories here.

Wonderful stories of some of the brave people who made the sacrifices in their own generation in order to build a better life for future ones. “What My Parents Believed” was a terrific prompt, Beth. There are many more stories, I’m sure, that you elicited with the same prompt and I’d love to read those too.

Thank you, Benita. I was pleased myself for coming up with this prompt. I’d started out thinking to ask writers for a piece about their religious backgrounds, but then thought, gee whiz, some of my writers may not consider themselves (or their ancesstors) “religious.” How about asking more broadly, what their parents believed? Bingo.

I loved those essays! They put names and histories to America being a land of immigrants.

Leave a Response