I posted last week about watching the documentary “The Most Dangerous Man in America,” about Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. In that post, I noted that it reminded me that as unsettling as the current times are, our current times have got nothing on that era. Along those lines, this piece in the NY Times—which imagines what 1968 would look like if you received news alerts on your smart phone back then—makes the same point about that uproarious year.

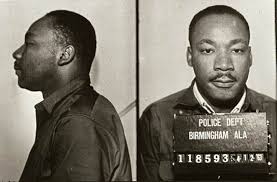

He had the courage of his convictions, no pun intended.

Back in 1968 I was going on 11 years old. But I’ve always been an old soul, and I grew up with a politically informed and outspoken mother and an older sister who was already volunteering for presidential campaigns at age 16. So I probably paid more attention to the news then the average kid my age did. Which is a longwinded way of saying, I was a bit of an oddball.

But an earnest one. I honestly tried to make sense of what was going on around me. I grew up in a suburb south of Chicago that was heavily populated with families who’d left the city of Chicago during a great wave of white flight.

Through grade school, junior high, and high school, I never had a single black classmate. There were tons of ethnicities, but none black. The”n” word and “n” jokes were thrown around frequently and loosely. Classmates talked of how scary their old neighborhood had become after it “changed.” There were hair-raising tales of being threatened and beat up. Some were pretty obviously exaggerated for effect, but some were undoubtedly true.

My classmates, of course, were often repeating what they’d heard at home. And they carried an anger, resentment, and hatred. Certainly, raw racism drove a lot of the exodus—white people in and around Chicago had essentially rioted more than once and terrorized people to keep their neighborhoods white. They didn’t succeed but they didn’t know, and I didn’t know, that back then, they and many of the black people who’d replaced them had both been victimized by some greedy slime balls who engaged in blockbusting, and bad government and institutional policy that produced redlining.

In my own home, there was no such sentiment about black people. My parents, first generation Americans, had landed in our town to follow job opportunities. My dad had gone to college on the G.I. bill, did a short stint as a teacher, and then got hired into a management-training program at a steel mill in East Chicago. My mom got a job teaching in the local school system.

I think of them—born to immigrants, children during the Great Depression, my mom taught Marines’ kids during WWII, my dad served overseas. And then Vietnam, civil rights, bra burnings, drugs, the sexual revolution, moon shots, TV, touch-tone phones!—and I realize now that they had to be just as bewildered back then as I can sometimes feel now (I really don’t want an Internet of Things, thank you).

There was no “n” word in our household. My dad did use the now politically incorrect “colored” to identify black people. But he didn’t have a hateful bone in his body. I think that Martin Luther King made them uneasy. Between civil rights and his opposition to a war they weren’t sure about themselves, I think they found MLK unnerving. For me, it seemed kind of simple: Every time I saw King on TV, there seemed to be some trouble and unrest around him.

So, to the 10 year old, he was simply a troublemaker.

And then he was murdered. And a lot of the country went up in flames. More than one classmate uttered something to the effect that King had gotten what he deserved, undoubtedly echoing a parent’s sentiment.

And I stayed up late to watch special news reports about King’s life and his work. It was the end of a certain kind of innocence.

Jeez I thought, he went to jail, he risked his life. He’s not the troublemaker I thought he was. I’ve had it all wrong. Things are not as they appear.

It was at once disconcerting and liberating. It changed how I looked at the world forever. It made me more skeptical about what I thought I knew and about what I was being taught in school, what people around me were saying. It made me angry and disappointed about my own country—and myself. But the story of his courage and resolve also made me hopeful. King and others had made a substantial difference. Courage and resolve were power. It’s worth fighting the good fight.

For all that, today, I say thank you Dr. King.

How lucky you were to have enlightened parents. I did, too, and I didn’t have to unlearn prejudice.

Thanks Judy. In truth, I’m still learning, but I started from a good point, that’s for sure.

Interesting. We had a black population in our south suburban community. There was plenty of bias and prejudice. But guess what? Even if you were a bigot, you made exceptions. It was rare to not have a least one friend from another race, someone in your gym class that you found exceptionally funny or someone in your homeroom class that you sat next to. You may still utter hateful words when you were with your own. But you made exceptions.

Al, Marland and I have talked at some length about your town and how it differed from mine. I think it had to have been healthy. Today, I’m happy to say, it’s a lot different in my home town and my high school.

Thanks, Mike, for your always honest writing. I’m older and my experience is different but in the end, the same.

Great writing, Mike. As I’ve aged, I’ve gotten a much greater appreciation for how quickly the Sixties happened and what a radical departure they were from the previous “consensus”.

[…] year about this time I wrote about how Martin Luther King’s death made an enormous impression on me. I was 10 years old when he died. And today, here we are. We want to think we’re done with […]

Leave a Response