I am pleased to introduce Barbara Hayler as our featured “Saturdays with Seniors” blogger today. Born and raised in California, Barbara moved to Springfield, Illinois in her forties to accept a position as Professor of Criminal Justice at University of Illinois-Springfield. She moved to Admiral at the Lake in Chicago when she retired, and is now putting her experience in academia to work, generously volunteering to lead the weekly memoir-writing class there in my abstentia as we shelter in place. Here’s the nostalgic essay Barbara wrote when given the prompt “A Change in Habit.” Enjoy!

Before Computers, There Were Typewriters

by Barbara Haylor

As a child I thought typewriters were exclusively business machines. Then I discovered that we had one in our home. Mom used it to prepare meeting agendas and minutes when she was President of the PTA. She typed up recipe cards to accompany her dishes to church potlucks, and sometimes even used it to write letters. But most of the time it was stored in a closet, tucked away on a rolling typing stand. When I was ten I moved the family Remington into my bedroom and taught myself to type.

I was horse-mad that year. I followed all the horses that were in contention for the Kentucky Derby, tracking their success in preliminary races through the spring. The races were covered in Sports Illustrated, which I checked out from the library. I couldn’t tear those articles out to save, so I typed out copies. I became quite adept at two-finger typing, but didn’t learn to type properly until I took a class in high school. My mother thought every girl should have a skill to fall back on “just in case.”

I did so well that my typing teacher thought I could have a great career as an executive secretary, and tried to track me into business math and shorthand classes. My mother put a stop to that. “This is a useful skill,” she told him, “but no vocational classes.” “Barbara’s going to college.”

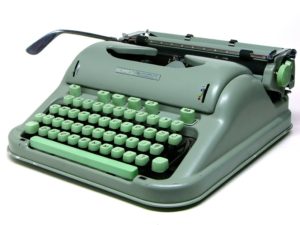

Three of my siblings had left home for college before me, and my parents sent each of us off with a good desk lamp and a typewriter. Handwritten assignments were acceptable in high school, but college required a typewriter. Mine was a gorgeous green Hermes portable typewriter, probably the best typewriter I’ve ever had. I later learned that it was a favorite of war correspondents because it was all metal and could take a lot of damage.

The study abroad program I went on during my freshman year at Lewis & Clark Colege in Portland, Oregon provided typewriters, so I didn’t take my Hermes with me when I went to France. I soon learned that instead of the standard QWERTY keyboard, French typewriters have something called the AZERTY keyboard. The “A” and the “Q” switch places, as do the “Z” and the “W.” This is supposed to facilitate typing in French (where Q is used much more often than in English) but it wreaks havoc on a touch typist who is used to typing without thinking. Just about the time I got comfortable with the French keyboard, I returned to the U.S. and had to relearn touch typing all over again.

Eventually my Hermes broke down, and no one could fix it. I flirted with a variety of alternatives: an electric portable that was prone to overheating, a variable spacing typewriter that I never got the hang of, a Selectric with that amazing bouncing ball, a memory typewriter that could erase up to a line of type on command. But they were mere machines.

I wrote my entire dissertation in pencil on yellow pads, but of course, it eventually had to be typed. That’s when I made the acquaintance of the dedicated Word Processing machine in the main office. State-of-the-art in 1984, it ran a now-obsolete program called VolksWriter and used 5” floppy discs the size of plates. When you inserted the floppy discs into a large reader that we called “the Toaster,” the screen displayed green letters on a dark background. Sometimes, after hours of typing a dissertation chapter into the machine, I would go home with visions of red letters on a light background dancing in front of my eyes.

My first personal computer was a generic Acer PC. Thirty-five years later, I have a Dell desktop that is slightly larger than the “Toaster,” with a thousand times more computing power. I have gotten used to composing on the computer, and love the ability to edit on the fly. But I’ve also had to get used to more typos, courtesy of autocorrect, and the autocratic rule of Bill Gates, whose Word program insists that “cancelled” is spelled with one “l.” I still sometimes write first drafts on yellow pads, but I got rid of my last typewriter – a portable Olivetti– when I moved to Chicago.

God help me if the power ever goes out!

Thank you for this. As a former legal secretary, I appreciate so much of her story!

Kind of makes you miss the rat-a-tat sound of all those clicking keys, doesn’t it? And then the rewarding “ding!” at the end.

This is the kind of thing one at first says to oneself: How can you write about that and make it interesting? Well she shows how. Brava!

Thank you, I so enjoyed this entry. And I did identify, as my mother taught me to type blindfolded at age 10 for similar ‘fall-back’ reasons.

Then came the computer and now I am dealing with three types of keyboards, the English one, the German one with its lovely Umlauts (öäü) and the extra ñ on the Spanish one. And then the self correcting…

Thanks for your comment, Bill. I was inspired to write on this topic after seeing the documentary film “California Typewriter,” which featured interviews with Tom Hanks and others who love their typewriters. My typewriters often felt like colleagues. My computer is just a useful tool.

I think many of us girls were encouraged to become typists for that reason, Annelore. Thanks for sharing your experience. Another oddity of the French keyboard is that it lacked the @ symbol (what we call the “at” symbol but which the French call “the snail,” because of its appearance). Not a problem on the typewriter, but definitely a problem when that same keyboard was adopted for computers! You had to know the secret code — CTRL-ALT-6, or something like that. Glad to hear that the German and Spanish keyboards avoided that problem.

Did I identify with this! My sister Peggi had a portable, Royal typewriter. I was not allowed to touch it. I couldn’t wait till I took typing lessons in high school. I memorized the keyboard, QWERT, etc. so I’d be ready when I took typing class senior year. Found out that’s not how it worked. I hated that bell at the end of each line. I wasn’t typing as fast as the others. I found myself panicking as I heard bell, after bell, after bell, before I heard my bell ding. I found myself listening for bells, unable to concentrate on MY typing. Eventually I became a decent typist. One job I had, used an electric typewriter with standard distance between keys. A HEAVY DUTY manual typewriter with wide spaces between keys. It was used to type the names directly on heavy duty cardboard files, instead of using labels. Then I would go home and type poetry of mine on the small-spaced portable Royal. Carbon copies were horrendous to work with. Smudges, using the skinny-roller eraser, then giving up and scratching the errors out with a razor blade. The worst was attempting to realign the original and 4 carbon copies. Wow, do I feel ancient!

Good story Barbara, it brought to mind my own struggles with typewriters. I remember an Olivetti and a Royal. Two things that went with the typewriters: the “white-outs” to correct errors, and the carbon papers to make copies.

Good story Barbara, thank-you!

Leave a Response