Tune in to hear Bob Eisenberg and me on WGN Radio Wednesday night, March 7 at 9 pm Central Time

March 4, 2018 • 3 Comments • Posted in careers/jobs for people who are blind, memoir writing, radio, writing promptsWhen Regan Burke and I were on WGN radio in January touting the benefits of memoir-writing, Justin Kaufmann, host of The Download, said over the air that “Stories by seniors make for great radio,” and that they should “have Beth on again with more writers from the memoir classes.” I contacted Justin and his producer Pete after the show, and guess what? He really meant it!

This Wednesday, March 7, another writer will be joining me for an interview with Justin Kaufmann on The Download on WGN Radio 720. If you caught the January show with Regan Burke, you heard how much fun we had. I’m expecting that again this Wednesday with Bob Eisenberg at my side – he and Regan are two of the writers from my memoir-writing classes whose stories intertwine with mine in my latest book, Writing Out Loud.

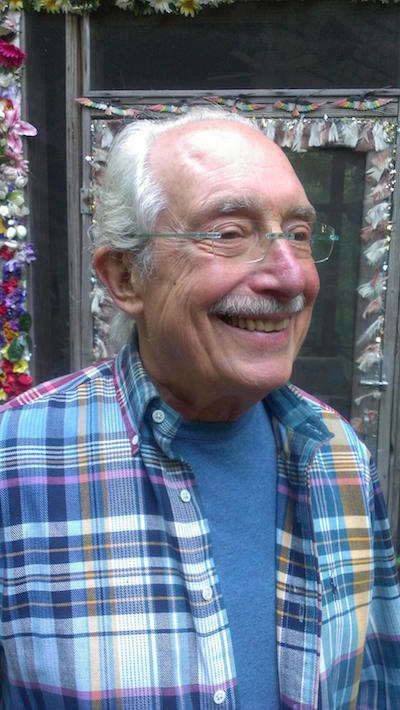

Bob Eisenberg

Bob shares stories in class of escapades growing up in Chicago’s Maxwell Street neighborhood with his buddies Squeaky LaPort, Da Da Hernandez, and Mario DeSandro. His nickname then was Bobby Butts Eisenberg, and together, they were the Pranksters. He describes Maxwell Street in the 1940s as a neighborhood full of Jews, Italians, and Mexicans.

When I assigned the prompt “What Are You Afraid Of?” we learned more of his story. “My mother died right after I was born,” he wrote. “I moved in with my mother’s mother until I was six. Then she died, too.” His answer to the prompt? He’s afraid to travel. “I don’t like leaving home.”

After finishing the school year in his grandmother’s neighborhood, tiny seven-year-old Bob was sent to military school. Sundry other relatives took him in after that, including his Uncle Morrie, who was a juggler/clown at Chicago’s Riverview Amusement Park.

“As I look back into my past I count six different grammar schools I attended and seven different families I lived with.”

Bob’s upbringing must have been tough, but when he writes about the people who took him in, he does so with a sense of joy and appreciation. He spent three years in the U. S.Army after graduating from Sullivan High School. Back in Chicago, he started styling and cutting hair, opened his own salon, and then studied with Vidal Sassoon to learn new methods. When asked how he ended up cutting hair for a living, Bob explains that it all started when he was six years old.

Bob is left-handed, and his stern first-grade teacher insisted he write with his right hand. Only problem? He couldn’t. He was simply incapable. And that meant he couldn’t write, do arithmetic, spell. With nothing to do, Bob was bored in school and was labeled a behavior problem. Whenever possible, he’d sneak the pencil into his left hand and draw the faces of his friends and teachers on his school papers.

“Cutting hair is just like drawing pictures of faces,” he tells me with a shrug. “All you have to do is add the hair.” After 60 years in the business, Bob has cut back to part-time and takes an afternoon off every week to join our Monday class. The ladies in that class tell me Bob wears his long white hair in a ponytail. Sure isn’t how I picture an 80+-year-old man who still makes his living cutting and styling hair! Bob married his wife Linda 30+ years ago , and their blended family of six children and numerous grandchildren provide him with plenty of other material for stories he’ll include in his memoir collection.

No doubt he’ll be sharing some of these stories on WGN Radio this Wednesday night , March 7 at 9 pm central. If you live far away and are one of those lucky people who received an Echo Dot or a Google Home Mini for a holiday gift, just say “Alexa” or “Hey Google” and ask them to play WGN. Or stream it on your computer or mobile device at http://wgnradio.com.

A piece in today’s New York Times caught my eye.

A piece in today’s New York Times caught my eye.