Dear dad, I'm sorry I was so hard on Ike

November 5, 2016 • 11 Comments • Posted in guest blog, memoir writing, politics, UncategorizedHere’s an essay by another writer in one of my memoir classes. After 80-year-old Bruce read this letter out loud about how he’s feeling now, a few days before the 2016 presidential election, I asked, “You miss your dad, don’t you?” Bruce answered, “I sure do.”

by Bruce Hunt

Nov. 3, 2016

Dear Dad:

It’s probably a good thing you did not live long enough to endure this presidential election. At the time of your death in 1979, you seemed to believe that civilization was in decline. I never quite knew whether your golden age was Greece or the Enlightenment, however. Maybe it was the Age of the Explorers? I do know this, though: you certainly would not be persuaded by Donald Trump’s declared intention to “Make America Great again.

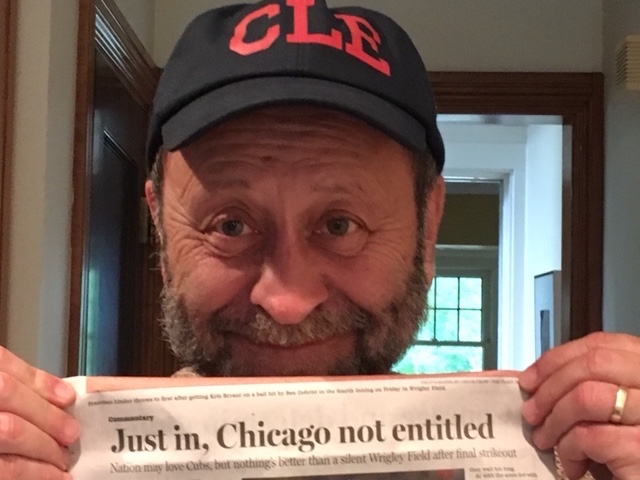

Frederick Atherton Hunt is pictured at about age 45. At that time, he was a

partner in his family’s law firm in Boston.

Were you still alive, you and I might engage in a lively discussion about whether there are any historical analogues to our present circumstance. Did the “Know-Nothings” of the late 19th century serve as precursor to the anti-intellectual tenor of the 2016 election? Was the language Taft and Teddy Roosevelt used to pillory each other comparable to the vile accusations that float around on social media?

The lack of civility would surely be disturbing to you. You belong to a long line of respectful citizens. Your devotion to the Republican Party stemmed in large measure from your appreciation for the decent men who held office in Massachusetts. Leveret Saltonstall was a distinguished senator, reelected a number of times. You were proud that Massachusetts voters elected Edward Brooke, the first African American senator in US history. Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. had a notable pedigree, although he was not a personal favorite of yours.

Democracy has always been messy. And you harbored secret (and sometimes not so secret) concerns about mob rule. I still recall your wondering whether perhaps a benevolent oligarchy might be the most effective government. Some say we are building a corporate oligarchy even now, with so much wealth in the hands of a very few families. I doubt that you would see this as progress or as benevolent.

I recall how torn you were in 1960 when you had to choose between a Harvard man who happened to be a Democrat, and A California Republican whose character you mistrusted. You voted for Nixon anyway.

You would be appalled by the character of the present Republican candidate. How he became the nominee is still a mystery to me. At first I thought it was a marketing effort to build the Trump brand. I still wonder if he cares a whit about governance.

Wait. I forget. You missed a major turning point in Republican political affairs.

Since Ronald Reagan (you likely will remember him as a spokesman for GE) became president, he made a casual comment: ”Government is not the solution, Government is the problem.” That quote has provoked a rash of cheap jokes, and it has made the phrase “civil service” the object of cynical scorn.

Elsewhere (see The First Time I Voted for President, Nov 8, 2012) I have acknowledged and apologized for my cavalier dismissal of Dwight Eisenhower as an inarticulate midwestern rube. That crass judgment stemmed from my intellectual arrogance and you called me on it more than once. In hindsight Ike got many of the big things right and certainly his temperament was more presidential than Candidate Trump, whose reputation is built on the 282 people, places, and things he has insulted on Twitter. (A communications vehicle too complicated to explain here.)

I hope you will not view this letter as an elitist appeal for more politically correct discourse while ignoring the real pain of people whose dreams have been dashed.

“Festina lente” make haste slowly you often cautioned me. I am hopeful about our messy democracy and I am looking forward to electing the first woman president. Now that is a topic I would be eager to discuss with you.