What do you call a blind woman with a photographic memory?

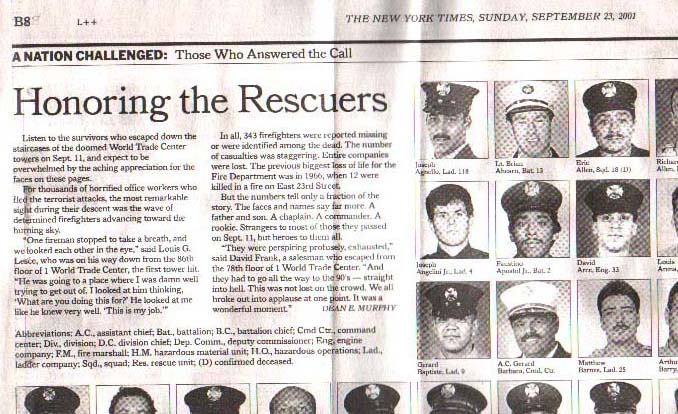

September 14, 2016 • 23 Comments • Posted in blindness, UncategorizedEvery September our city honors five Chicago artists and cultural institutions at a free “night of stars under the stars with live performances and videos” at Millennium Park. I feel a far-fetched fondness for one of this years honorees. You might be surprised to find out which. Is it:

- Blues legend Buddy Guy

- Photographer Victor Skrebneski

- Improv and sketch comedy theater The Second City

- Actress, educator and theater founder Jackie Taylor, or

- Museum founder and educator Carlos Tortolero?

Well, my winner is…Victor!

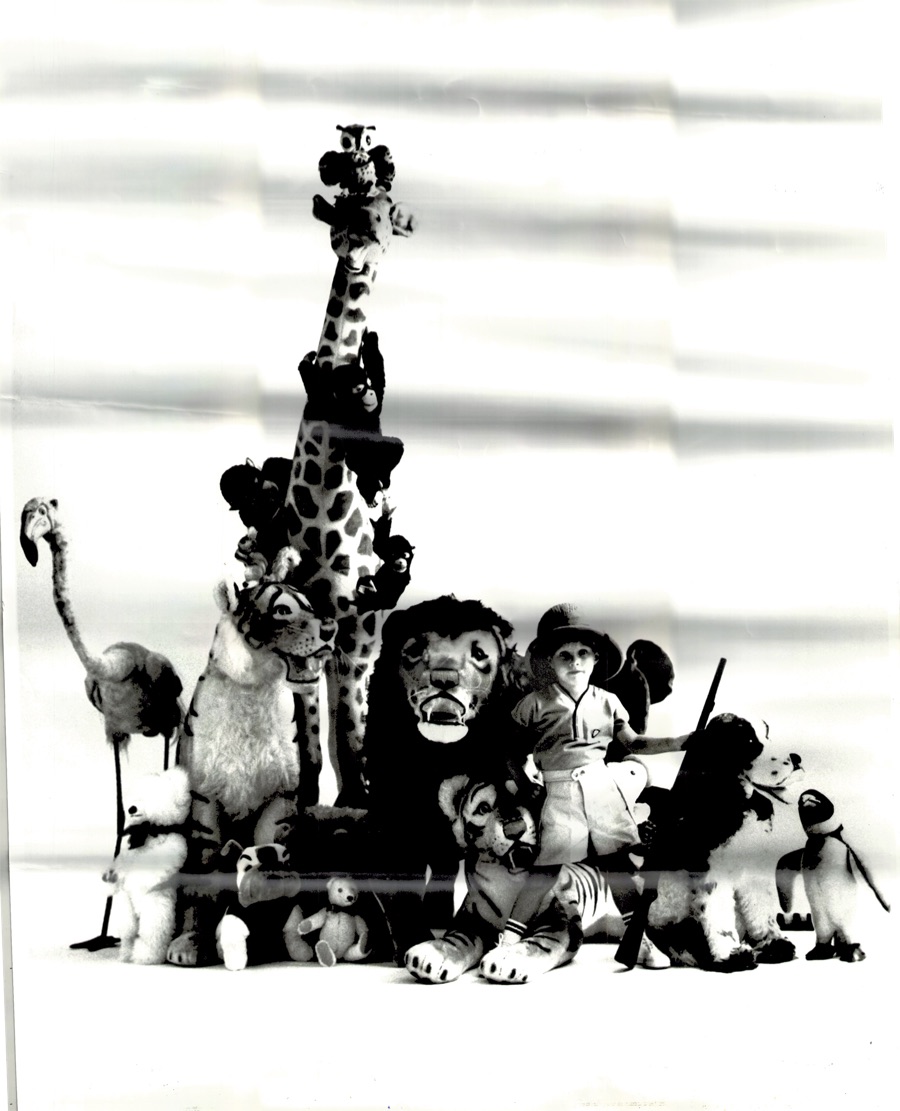

That’s Matt on the lower right.

How could a blind woman have a fondness for a photographer? I’ll try to keep my answer short.

One of my best friends from high school was Matt Klir. We met when I was 16. I could still see then, and I was the librarian for our high school band. Matt was a year younger, played the drums, and he’d signed up for “summer band” that year. When we discovered we both were bicycling from miles away to attend summer band practices, we started riding together. A friendship was born.

Matt’s house became my second home. He and his two sisters were beautiful. His parents were divorced, and the three of them lived with their young vivacious mother in a fancy 1970s sprawling home. Every single time I visited (and that was lots of times!) I’d venture into their dining room, edge around their tres modern glass dining room table and gawk at the huge black and white photos displayed on their walls.

Matt and I were together constantly in high school,but we didn’t “date.” We never even kissed. I graduated in 1976, and on prom night that year we pooled our money and bought Elton John tickets instead. Front row. I wore the polyester red, white and blue halter-topped bridesmaid dress from my sister Marilee’s Bicentennial wedding that year. Matt wore a powder blue leisure suit. He brought a dozen roses along, and when I handed them to Elton John’s lyricist at the end of the concert, Bernie Taupin said, “Thanks, love.”

Matt and his two sisters had been childhood models. News of Victor Skrebneski’s honor tonight motivated me to contact Janine and Crystal to reminisce. When I asked if either of them still had a copy of the huge b&w photo Victor took of Matt, they knew immediately which one I was talking about.

“I remember when Matt was at that shoot,” his older sister Janine wrote in an email. “Victor’s studio was so home-like. Lots of ladies and other people hanging around, comfy couches, along with his impressive photo studio in the main room.” Janine found the photo of Matt in her basement workshop. “It was rolled up in a box with other old pictures.” she had the photo straightened and scanned, and here it is.

I can no longer take in the photo Victor Skrebneski took of Matt back in the early 1960s for a Marshall Field & Company Christmas ad. Victor’s work is very memorable, though. I can still easily see my friend Matt as a youngster. He’s in his safari hat, surrounded by stuffed animals.

Matt died of AIDS 24 years ago, on September 17, 1992. I still miss him. I’ll be at Chicago’s Millennium Park for the 7:00 event tonight honoring my friend Matt — and the photographer whose work is still so clear to me. Thanks to Victor Skrebneski’s gift and his keen eye, I can still picture young Matt.

Vividly.