I know what a slider is at White Castle, but…

October 4, 2015 • 18 Comments • Posted in baseball, blindness, Mike Knezovich, radio, Uncategorized, writingI’ve learned a lot about baseball from my husband Mike Knezovich over the years, but one aspect of the game that still confounds me is pitching. Which direction do curve balls curve? What’s the difference between a slider and a cutter?

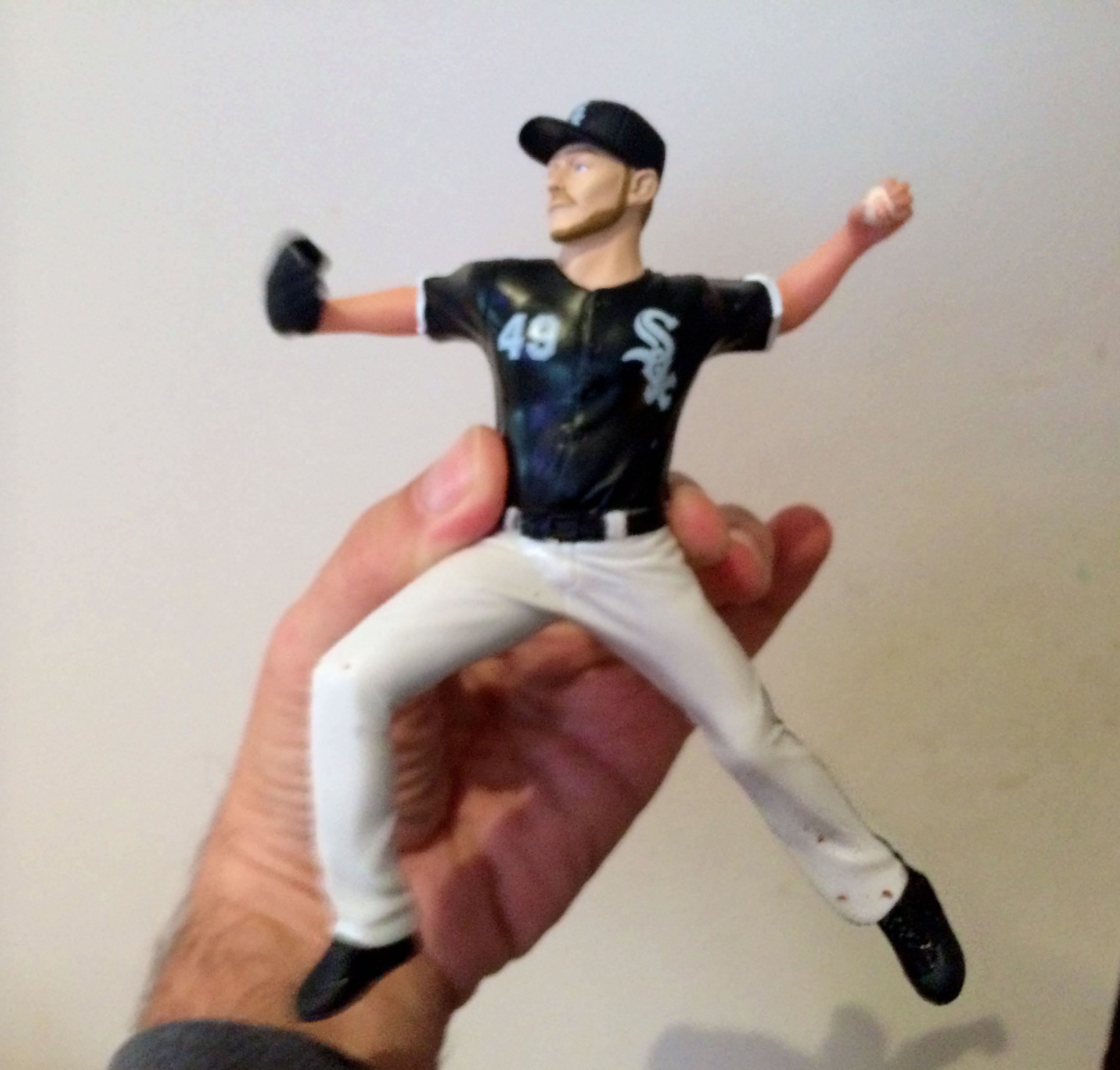

Thanks to our generous friends Don Horvath and Juli Crabtree, we were able to enjoy last night’s White Sox win against the Detroit Tigers. Fans were given “Stretch Sale toys at the door to commemorate White Sox pitcher Chris Sale’s single-season record-breaking 270 strikeouts. I fondled my Stretch Sale throughout the game, and now I finally understand why legendary Los Angeles Dodgers baseball announcer Vin Scully refers to him as “Mr. Bones” and others liken the 170-pound 6’7” left-hander’s wind-up to a strained inverted w “ akin to a scarecrow.”

Mike is always around to answer my baseball questions, and good radio announcers like the Brewers’ Bob Uecker, the Tampa Bay Rays’ Dave Wills, and Giants’ Jonathan Miller have been a big help in my understanding the game, but I am still left to wonder how it is that baseball fanatics and skilled announcers can accurately predict that the next pitch will be a change-up or a braking ball, or more simply, a strike or a ball.

And so, at this time each year, as we enter the playoffs, I turn to literature to help me better understand how pitching works. And year after year, literature has disappointed me.

Perfect I’m Not by David Wells taught me more about beer, brawls, and backaches than about pitching a baseball. I found Jim Bouton’s Ball Four, annoying, probably because Jim Bouton reads the audio book himself, and he’s pretty arrogant. Author Buzz Bissinger follows the St. Louis Cardinals through a 2003 three-game stint against the Chicago Cubs Three Nights in August. The book was entertaining because I’d listened to that three-game series myself on the radio (2003 was the year Mike and I moved to Chicago) but I would have learned a lot more about pitching if Bissinger’s book had focused on Cardinal pitching coach Dave Duncan’s decision-making rather than fawning over Tony La Russa.

I’d just about given up learning anything about pitching from reading books when I opened up my daily Writer’s Almanac online on Saturday, September 19 and learned it was Roger Angell’s birthday that day. The almanac said Angell was born in New York in 1920, and his mother and stepfather were well known in the literary world. His mother was Katharine Sergeant Angell, the longtime New Yorker fiction editor, and his step-father was E.B. White, the essayist and children’s author.

The almanac said Roger Angell started working for The New Yorker in 1956 and is best known for writing about baseball. “He was 79 when he published his first full-length book, A Pitcher’s Story.”

What? A Pitcher’s Story? I looked for Angell’s first “full-length book” on BARD, the Library of Congress National Library Service that provides audio books free of charge to people who are blind or visually handicapped, and bingo! A Pitcher’s Story was available. It did not disappoint.

Example? In Chapter 7 (called “Get a Grip”) Angell is sitting in the Yankee bullpen and asks pitcher David Cone to describe how he holds a baseball for each pitch, and what he expects to happen next. He asks readers to put down their book and “root around the house for an old baseball.” I did as I was told and found mine in my top dresser drawer, signed by White Sox pitcher Roberto Hernandez after I met him in a sports store in the late 1990s and asked to feel the circumference of his upper arm with my two hands. Oh, my.

But back to Roger Angell’s “A Pitcher’s Story:

The ball, it will be seen, keeps representing a horseshoe curve of stitches when rotated. There are four of them. If we grab a horseshoe so that the first and middle-finger fingertips just slip over the top broadmost curve of the stitches, a red row of stiching will appear to run down the aver side of both fingers, as if to frame them. With these two fingers slightly parted, the odd conviction comes that you’re on top of the ball.

”This is the two—seamer,” Cone tells Angell in the book. “You’ve got it!” Cone describes how to adjust the two-seamer into a four-seamer, and how four-seamers are meant to cut the wind, while two-seamers tend to sink. “The one-liner is just a variation on the two-seamer,” Cone says. “Let your finger slip a little toward the wider white area of the ball, and you press down more with your forefinger.” “They moved on from there to the curve, the slider, the splitter, and Angell acknowledges that he’d hoped to sit down with Cone before one of his starts so Cone might go over one of the other team’s batting orders, describe each batters’ strengths and weaknesses and let Angell know his plans. “It was a dumb idea,” Angell concedes, and while I get back to playing with my Chris Sale doll, I’ll leave you with Roger Angell explaining why that was so dumb:

Each hitter and turn at bat presents the pitcher not with a fixed offensive array, but with something fluid and conditional, a cloud chamber of variables. The count, the score, the inning, the number of outs, the position of base runners, the umpire’s strike zone, capability of the outfielders, the quickness of the catcher, how much you can trust this particular receiver to handle the splitter in the dirt, the runner at third, how this next hitter was swinging in his last at-bat and the one before that.

Let the playoffs begin!