Whitney and Beth, live at Biograph Theatre

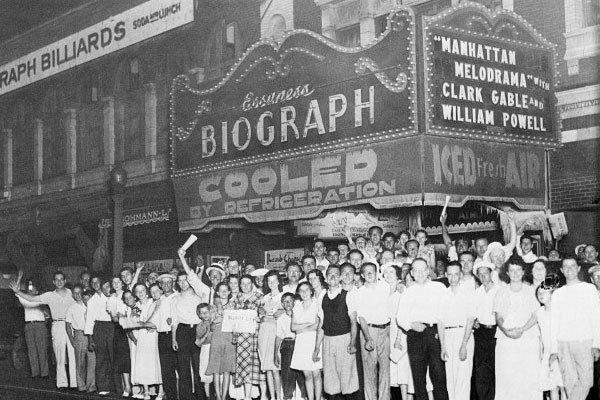

August 19, 2015 • 13 Comments • Posted in blindness, public speaking, UncategorizedFor eighty years now, Chicago’s Biograph Theatre has been known as the movie house where FBI agents gunned down bank robber John Dillinger. After our performance this past Monday night, though, maybe the Biograph will start being better known as the theatre where Beth Finke and her cute Seeing Eye dog Whitney got their stage debut.

Let me explain. The Biograph was a movie Theatre for 70 years after Dillinger was killed, but in 2004, a regional theatre here in Chicago called Victory Gardens refurbished it to put on live productions there. Arts organizations all over Chicago are sponsoring special events, lectures and workshops this year to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and when Victory Gardens Access Project opted to sponsor a workshop for “front of house” (FOH) staff from theaters all over the city, I was asked to sit on a panel there with three other disability advocates to give tips on some of the special needs people with disabilities might have when we attend live performances.

Front of House encompasses all the things happening with the audience in the lobby and at the concession areas before, during, and immediately after a show — anything from selling tickets to handing out concessions to ushering. People who work front of house tend to do so because they enjoy working with people, they love live theatre and they’d like more people to come out to support and enjoy performances. From what I witnessed at the workshop Monday night, they are keen to include more people with disabilities in their audiences, too — I was pleasantly surprised by the large turnout. Nearly 100 FOH staff members were there, representing everything from storefront theatres to art museums to established art programs.

Whitney and I arrived an hour before our panel, and when we walked into the Biograph’s refurbished and stunning lobby I discovered two sign language interpreters giving a workshop about the things theatres should look for when hiring sign language interpreters for their productions. The presenters used their voices as they signed, which made it possible for a woman like me to eavesdrop. I did, and learned that the best theatre interpreters are ones who:

- avoid signing every word — it’s more important to convey the overall story and allow the action on stage to tell the rest

- prepare in advance — a presenter said she studies the written script and listens to recordings of the play for weeks ahead of her sign language performances and attends rehearsals and productions ahead of time to get a sense for the timing and determine which signs to use on the day of her sign language interpretation

- agree to work in teams if the play has many people on stage at once who are talking over each other

- use subtle movements, like widening their eyes or raising their eyebrows to add meaning to the words they’re spelling out

- wear extra dark lipstick so audience members capable of reading their lips can see them better

- wear dark clothes if they’re very light skinned so readers can see their hands

- wear light-colored clothing if their skin is dark so readers can see their hands

- take rings and bracelets off before they start signing

So many things I hadn’t ever thought of! Our panel afterwards went well, and it was a thrill to be on the Richard Christiansen stage at the Biograph Theatre with playwright Mike Irvin (founder of Jerry’s Orphans, which organizes annual protests against the Jerry Lewis telethon), Rachel Arfa, J.D.,(a staff attorney at Equip for Equality, a legal advocacy organization that advocates for the rights of people with disabilities) and Evan Hatfield (Steppenwolf Theatre’s director of audience experience).

Mike Irvin uses a wheelchair, Rachel Arfa uses bilateral cochlear implants, I use a Seeing Eye dog, and Evan Hatfield introduced himself by telling the audience he “Doesn’t identify as having a disability.” We took off from there.

The evening ended with answers to questions Front of House staff members in the audience had about touch tours before shows, wheelchair-accessible stages, captioning technology, and person-first language like “Mike uses a wheelchair” rather than “wheelchair-bound Mike.” Audience members shared the challenges and successes of accessing arts programs, the night flew by, and I think (hope!) we made a small difference.

Guess I can find that out the next time I attend a performance in Chicago — and I hope that’s very soon.