Here's why Lionel went back to conventional trains in 1945

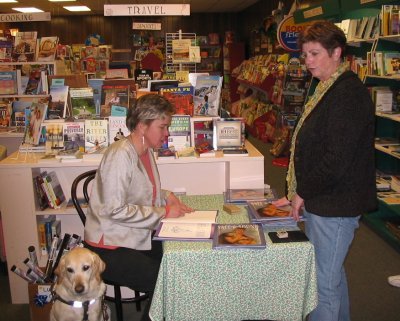

August 20, 2014 • 11 Comments • Posted in careers/jobs for people who are blind, memoir writing, UncategorizedWhen I assigned “The Best Job I Ever Had” as a topic for the writers in my memoir classes, Hugh went home and started making a list. “I wrote down every place I’d ever worked,” he said. “This one kept coming up on top.”

His essay opens in the summer of 1943. Hugh was 11 years old, American soldiers were fighting in World War II, and everyone here at home was rationing. “Metal was necessary to use in making all kinds of military equipment,” he wrote, describing scrap metal drives, manufacturers of pots and pans switching to making mess kits for soldiers, Boy Scouts collecting tin cans that would eventually be turned into airplanes.

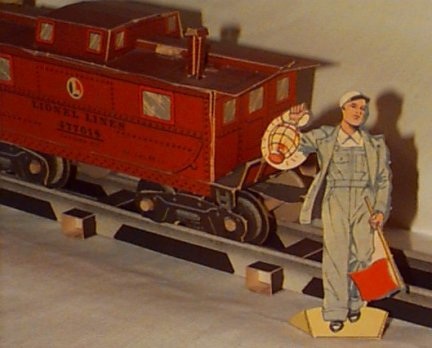

Less important businesses like toy manufacturers had to stop using metal altogether, and Hugh said it hit the Lionel Train company hard. ”They knew they wouldn’t be able to sell any new electric trains to run around the Christmas Trees.” What to do? Execs at Lionel put their heads together and hired a novelty designer who came up with the answer: paper trains. From Hugh’s essay:

My mother worked for a market research firm that was hired to test whether the paper trains were easy enough to assemble and to produce enough samples to show to the retail stores. Mom, in turn, enlisted my 14-year-old brother and some of his friends to assemble a bunch of paper trains. Needless to say, although I was only 11, I tagged along and got hired, too.

Hugh describes the flat 11×15 lightweight cardboard sheets he and his buddies worked with: each sheet had train parts printed in authentic colors, and Lionel’s insignia was on every page. “The kit included an engine, a tender, a boxcar, a gondola car and a caboose,” Hugh said, stopping to take a breath before continuing to read his essay out loud in class. “It also had a crossing gate, a crossing signal and enough paper ties and rails to make a good sized circle.” The wheels were laminated cardboard, too, but the axles were little rods made of wood. “It took us many tries to be able to assemble the cars and the track, but eventually we became pretty good.”

It was difficult to find any information online about these 1943 paper trains, and I might have started worrying about Hugh if I hadn’t found a Lionel Wartime Freight Train page on Wikipedia. The Wikipedia page confirmed Hugh’s story and reported that paper trains did well financially in 1943. After buying a paper train for their children, though, most parents became so frustrated by the assembly process that they gave up on putting it together and threw it out.

Hugh and his buddies got paid for testing the paper trains ahead of time, but he couldn’t remember how much they earned for their work. “It must have been by the hour,” he wrote, realizing now that if it was by the piece, they wrecked so many that they never would have made anything.

”It was really fun being with our friends and playing at putting these things together,” Hugh wrote. “And I got paid!” The all-paper product train sold for a dollar during the 1943 Christmas season, but it went off the market after that due to poor customer response. Seventy years (and many, many jobs) later, however, Hugh maintains that getting paid to put those paper trains together “is still The Best Job I Ever Had.”