Mondays with Mike: We can do this

July 22, 2019 • 4 Comments • Posted in Mike Knezovich, Mondays with Mike, parenting a child with special needs, politicsAmid the inflamed political climate that is being deliberately sown, it’s easy to get so distracted that we’re never, ever discussing substantive issues. It’s so easy to get caught up in name-calling and labeling, instead of having respectful back and forth.

And from what I’ve seen, either the Democratic Party and its constituents will do it, or no one will. (I’m happy to consider voting for a Republican—the next time I recognize one that’s actually, well, a Republican.)

On the Democratic side, we have an opportunity to discuss substance with each other, and try to squeeze it out of the candidates. This all came to mind when I witnessed a minor skirmish between some Democrats.

One was chastising Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for off-handedly dismissing Joe Biden’s remark to the effect that a lot of people would be heartbroken to lose their private insurance under a Medicare-for-all scenario. This same person also expressed general angst about AOC and her cohort turning off middle-of-the-road Dems and other voters.

And then the predictable backlash against “moderate” Democrats.

And off we went into nowhere.

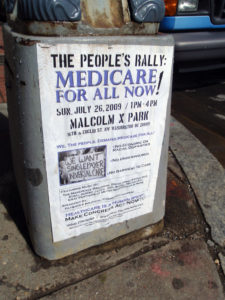

To me, Ocasio-Cortez can and should speak up on anything she wants. And by my lights, she’s good at it. I don’t think she and her cohort and the candidates who support Medicare-for-all are naive dreamers. I’m glad they care about the issue.

On the other hand, I don’t support Medicare for All. And I don’t think that those who do support Medicare-for-all should consider those of us who don’t’ support it as sellouts.

If there’s been one issue that I’ve consistently cared about for most of my adult life, it’s been health care. It remains so. As in, everyone should have a humane level of coverage. What’s humane? As an example, I’d suggest the level that the small non-profit I work for could be used a baseline for discussion. That’s for another time.

Beth and I became heavy-duty users of our health care “system” starting in our twenties. Actually, she’s been at it since she was seven, and diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. On our honeymoon, she started seeing spots. Months of treatments and hospital stays ensued. Two days before our first anniversary, we learned she’d never see again.

And then Gus was born with a myriad of health issues that we deal with to this day.

We were lucky. Beth and Gus were covered throughout. If these things had happened at different times in our lives, we were cooked. But even being lucky, we ended up in enough debt to take years (and a lucky break with a startup company) to erase. And even with that lucky break, I can’t tell you how much time I have spent trying to understand bills, coverage, reconciling conflicting info from the provider and the insurance company, etc. And of course, we all live dreading losing the insurance.

Back in our 20s, all our contemporaries knew about health insurance was that they had it. But when I’d tell them what it was like to use it, their eyes would gloss over, and you could see the thought bubble above their heads: “Mike’s going on a health care rant again.”

Back then, to anyone who’d listen, I argued for a single payer system. I completely see the attraction—maybe especially to cut down on the insane billing bureaucracy that private industry has given us.

But I don’t support single payer anymore. Those who do are good by me. I just strongly disagree with the Medicare for All thing for several reasons.

First, from a logistical and economics point of view, shutting down a giant industry while expanding an already enormous bureaucracy is going to be an enormous, disruptive task that I fear would be an enormous mess. (Granted, some displaced workers would be recruited to the expansion of Medicare.) But it’s a gigantic and complex undertaking, and none of the proponents have indicated they fully understand that. Nor have they sketched an outline of how it could be phased in with minimal disruption. I suspect it’s because…it’s difficult to impossible.

Politically, most people simply don’t want to switch their insurance plans involuntarily. You’re asking them to give something up and telling them, “Don’t worry.” And we don’t exactly have a great track record here. Obamacare promised that no one would lose their current plan–and that was untrue. Many people remained insured but with lesser plans. So people are more skeptical than ever about claims about what they’d get. I don’t believe the support will be there when push comes to shove.

The thing is, Europe has had universal coverage for decades. But single-payer is a complete exception when it comes to achieving universal coverage.

Their systems, by my lay study of them, rely on heavily regulated private insurers. They let those with means buy more than minimum coverage.

So, I say beef up Obamacare, ratchet up regulation of existing insurers, a la most of the countries that have universal health care. And by hook, or by crook, shoehorn a public option in, which, if it works, would move us toward single payer, and if it doesn’t, it doesn’t.

All that said, I welcome anyone to address the concerns I’ve raised—to offer how the problems I perceive with Medicare-for-All can be solved. Let’s not forget that we all want everyone to have coverage.

More broadly, the concept of civil political discussion in the commons has disappeared. That means on the blue-state side of things, it’s on us to show, well yes, that concept is alive and well.