Mondays with Mike: Hail the Fourth Estate

June 25, 2018 • 3 Comments • Posted in Mike Knezovich, Mondays with Mike, politicsIn the age of “fake news,” ultra partisan publications and broadcast channels, and nutjob websites, we—for the time being, anyway—enjoy a pretty robust press. It’s really easy to dump on “the media,” but that’s painting with too broad a brush. Good journalism and good writing are hard work. A lot harder (and generally, more time-consuming and therefore more expensive) than bad journalism.

It takes some work and some luck to find good stuff, but it’s out there.

Awhile back I bumped into a non-profit online publication called The War Horse. It’s chock full of reporting on the military, much of it by veterans or current service members. It provides what I think is a very useful and non-ideological point of view on defense and military issues, as well as the personal issues military members and family face. Check it out at https://www.thewarhorse.org

I also follow their Facebook feed, which spreads coverage from a range of publications on military matters. One headline recently caught my attention:

15,851 US service members have died since 2006. Here’s why.

At first, it was the number itself—higher than I would’ve imagined—that piqued my interest. But another number was just as interesting (and sobering): Of the 15,000+ who’d died, only 28 percent were deployed on the battlefield. I’ve always understood that apart from war, just beingin the service can be dangerous. My brother-in-law Rick flew helicopters, among other things, and though he was always circumspect in talking about it, it was clear to me that what were called training exercises were hair-raisingly dangerous. Anyway, the article appeared in Military Times, give it a read if you have a moment.

And then there are two pieces from our pal Lydialyle Gibson, a tremendous writer and reporter and just a swell gal from the South. She came to Chicago for a journalism education at Northwestern and after graduation sworked at a community newspaper that covered our Chicago neighborhood, then for the University of Chicago Magazine and now, at Harvard Magazine. She loves her gig because she gets to talk to people who do remarkable thjngs.

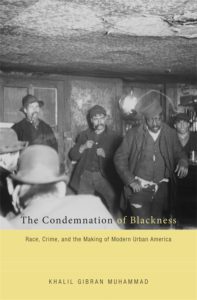

One of them being Khalil Gibran Muhammad, a Harvard scholar who wrote a book called “The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern America.” It looks at how public perception of crime in black neighborhoods largely populated by blacks who came North during the Great Migration differed from the perception of crime (and its roots) among the waves of Irish and European immigrants. More important, how the perception drove policies and government programs that treated the latter group much differently than the black communities. Lydia’s article gives a pretty full—and painful—accounting of those differences. It sure rang true and consistent with the various narratives I grew up with. We still have a lot of work to do. I hope you’ll give it a read.

And one more plug for our friend: She profiled Tom Nichols, the author of “The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Expertise and Why It Matters.” The book explores ignorance and unreason in American public discourse—these days, that’s a lot to explore. He’s a very interesting guy, a lifelong, serious and intellectual conservative, and a member of the Never Trump club. He’s also on the faculty of the U.S. Military Collges, and previously worked as a nuclear policy analyst and Soviet specialist during the Cold War. The guy’s hardly a red meat ideologue of any stripe. I hope you’ll give it a read, too.

And remember, good journalism is hard, but it’s out there, thanks to some really dedicated people.