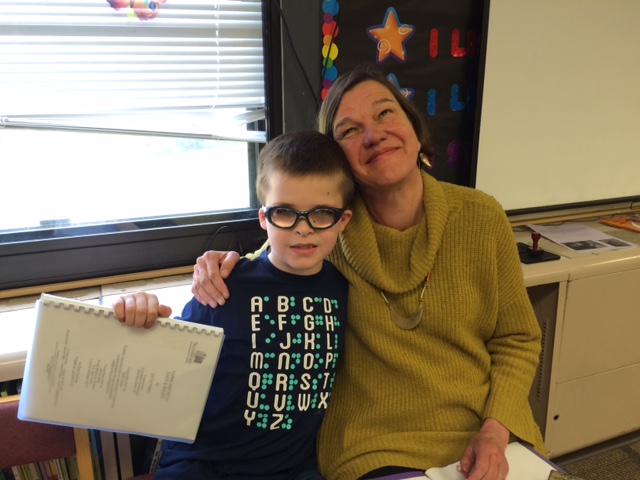

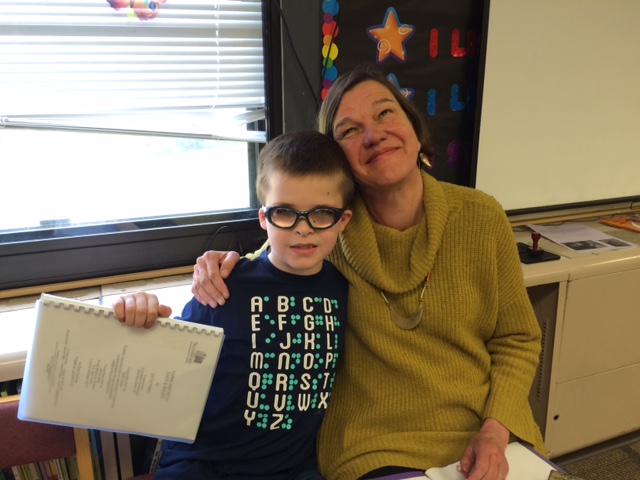

Last week my Seeing Eye dog and I met a second-grader I’ve been hearing about for years. Bennett is a student at Tess Corners Elementary School in Wisconsin, and Whitney and I spent the entire day at his school Friday.

That’s Bennett and me. He’s holding a Braille copy of Safe & Sound.

I first heard of Bennett back in 2013, when his mom wrote to tell me how much her five-year-old enjoyed reading the Braille version of my book Safe & Sound. From her note:

“Bennett was so excited about the book. He told me, “I loved that book you got me. It’s a true story, mom. And no one ever writes true stories for kids about people who are blind like me.”

A stellar review — from an expert.

I kept up with Bennett and his mom via email ever since, and in 2014 I wrote a post about Bennett and his parents traveling from Wisconsin to the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh to have Dr. Ken Nischal, one of the world’s foremost children’s eye specialists, try a cornea transplant in Bennett’s right eye.

Bennett told me Friday that his vision improved in his right eye after the surgery. “But just for a little while.” Whitney and I got to his Wisconsin school just in time to meet Bennett in person — he’s returning to the University of Pittsburgh this week for more tests.

Bennett and I spent the first hour of the day together with an older boy who has visual impairments — Michael came in special on a short field trip from his middle school. They both had questions about Whitney, and I let each of them inspect her harness and take a few steps with her. After that, we were off to the first presentation.

Tess Corners is a happy school. The teachers expect a lot from their students, and they enjoy their work — I heard smiles in their voices. Their principal taught first and second grades for decades before accepting an administrative position there, and she told me she still misses teaching sometimes. The school librarian had read Safe & Sound out loud to every class before Whitney and I arrived, and with Bennett at their school, the kids at Tess Corners already know a lot about blindness.

They still had questions, though. Bennett and Michael were at my side for the presentation we gave to all the second graders (including Bennett’s second-grade class), and during the Q&A, I answered each question first, then passed it on to my young assistants.

“Can you see at all?” one girl asked. “When I open my eyes, all I see is the color black,” I told her. Michael said, “I can see some things if I hold them really close.” Bennett said, “I can kind of see light, but everything is blurry…like a cloud.”

Another child asked “How do you read if you can’t see?” I described audio books and my talking computer, Michael touched the screen on his iPad so we could hear VoiceOver, and Bennett showed off his Brailliant, a refreshable Braille device.

That’s the Brailliant device Bennett uses.

Michael eventually had to return to middle school, but Bennett stayed in front with me long enough to read aloud to his classmates from the Braille version of Safe & Sound. His composure and confidence was remarkable — a credit to his fellow students, his family, the teachers and staff at Tess Corners, and, especially, to Bennett himself.

Bennett left with his second-grade class after that, and Whitney and I presented to the other grade levels on our own. I met up with Bennett again one last time during his lunch break — he wanted to show me how to use a Brailliant.

A Brailliant is an electronic device people who are blind use to read with their hands. The Brailliant transforms the words on a computer screen into small plastic or metal pins that move up and down on a flat panel attached to the computer. Bennett explained how he places his fingers on the panel to read the Braille characters formed by those pins, and then demonstrated by reading a line of text out loud. I’d never seen, errr, felt, such a thing before.

My Braille skills are poor. Bennett used the keys to tap out secret messages and pass the device my way so I could read them in Braille. He couldn’t help but notice — and chuckle — when I struggled to decipher his big words.

Bennett dumbed it down then and used shorter words. He placed my hands on the keys to show me how to compose and send a Braille note back. The blind leading the blind for sure. We exchanged “refreshable Braille notes” for the rest of the lunch hour.

Today fewer than 20 percent of blind children in this country learn to read Braille. Bennett uses VoiceOver to check his school assignments, and he listens to audio books sometimes, too. But he and his teachers know that if he doesn’t learn to read Braille, he won’t learn to spell correctly. He won’t know where to put commas, quotation marks, paragraph breaks and so on. Bennett has already tackled a lot of this stuff.

It’s true I’m not proficient in Braille, but the little I know sure comes in handy when I label CDs, file folders, ID cards, buttons on computers and other electronic devices. My Braille skills are useful on elevators, too, and it was rewarding to know enough Braille to exchange secret messages Friday with that bright, curious, cute — and patient — second-grade boy I’d been hearing about all these years.