Now that I think of it, maybe he meant funny, as in "odd"

November 26, 2013 • 19 Comments • Posted in blindness, book tour, Flo, public speaking, Uncategorized

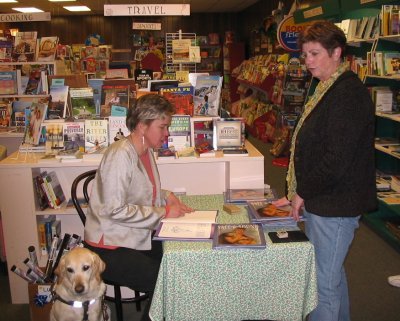

That’s Jenny with Hanni and me at The Bookstore in Glen Ellyn.

After a presentation I gave at The Bookstore, a Glen Ellyn reporter approached my longtime friend Jenny Fischer, who works there, and asked, “Was she funny like that when she could see?”

That wasn’t the first (or the last) time someone has said something along those lines. It’s tempting to look for an upside to disability. That hardship can make you tougher. That blindness can make you a better listener. More humble. Or, I guess, make you funny.

The perception that becoming disabled changes ones character is one I’ve always struggled with, and have always been skeptical about. And Monday, listening to the radio, I finally came to understand why. I happened to tune into NPR that day just in time to catch a Fresh Air interview with journalist James Tobin about his new book The Man He Became: How FDR Defied Polio to Win the Presidency. I loved the author’s response to a question about whether polio had made Roosevelt stronger and more determined as a president. “The question doesn’t make sense to me,” Tobin said. “People either have those capacities, or they don’t.”

He acknowledged that a crisis might reveal a person’s character in sharper relief, and that perhaps Roosevelt’s disability allowed him to see himself for the strong person he was, but still, the author remained adamant that Roosevelt was a strong and determined man long before he was stricken with polio. “It gave him a kind of confidence in his own strength,” he said, adding that perhaps that sort of confidence might only come when a person is tested.

Whatever courage, humility, attentiveness, or sense of humor I have, I owe not to blindness, but to my marvelous mother. Flo raised me — and my six older brothers and sisters — that way. .

I’ve written before about our father dying when I was three, and Flo using her strength and determination and courage to pass a high school equivalency test while still grieving, transform herself from housewife to full-time office clerk and work until her 70s to raise us on her own. Children learn a lot from watching their parents.

Flo is 97 years old now, and we’re still learning a lot from her. She’ll be heading to Chicago Thursday to share Thanksgiving dinner with my sister Bev, her husband Lon, our neighbor Brad, me and the magnificent chef, my husband Mike. I have a lot to be thankful for. Happy Thanksgiving!