The heart and soul of Francis W. Parker School

March 22, 2013 • 7 Comments • Posted in guest blog, Uncategorized, visiting schoolsThis week Judy Roth, one of the writers in my Thursday afternoon memoir-writing class, arranged for Whitney and me to visit the school where her grandson Davin goes to kindergarten. My friend Carol drove us to Francis W. Parker School and agreed to write a guest post about our morning together there.

My morning at Francis W. Parker School

by Carol Dorf

When I heard Beth was going to speak to kids at Francis W. Parker School, my hand immediately shot up to ask if I could accompany her. Sure, I wanted to experience Beth interacting with kids, but, truth be told, I really wanted to see what kids who attend one of the most prestigious private schools in Chicago are like. From the school Web site:

Colonel Francis W. Parker, influenced by the educational theories of John Dewey, envisioned a school that held the child at its very center. His fundamental belief was that learning could be fun and proved his point, not by theories on child psychology, but with actual classroom demonstrations. Colonel Parker believed that education included the complete development of an individual — mental, physical, and moral. Through the educational journey, students would develop in to lifelong learners and active, democratic citizens.

Colonel Parker believed that these great citizens must use their knowledge to improve the community– to make things better, more fair and pure. Parker students would graduate, not only with vast knowledge, but also with heart and soul.

Francis W. Parker School was, shall I say, quite lush: carpeted hallways, perfectly appointed decorations on the walls, modern desks, fabric lounge chairs. This was the crème de la crème.

The kindergarteners shuffled into the auditorium, and once they found their seats I could see heads bobbing and stretching to get a look at Beth and Whitney. Some kids were literally on the edges of their seats in anticipation of what would come. They waited patiently as Beth did her shpiel, and then, like mini Arnold Horshack’s, two dozen hands went up.

This was the moment I was waiting for. What questions would these “senior kindergarteners” ask: “How do you know the maid has done a good job if you can’t see?” “Who walks the dog for you?” Yes, I admit I was expecting a bunch of precocious kids asking questions that reflected their seemingly privileged lives. I pre-judged, and boy, was I wrong. What I heard instead was exactly what you’d expect from any 5-year-old:

- How do you write if you can’t see?

- Can you tell what I look like?

- If you can find your wallet, How do you know what’s in there?

- How do you make food?

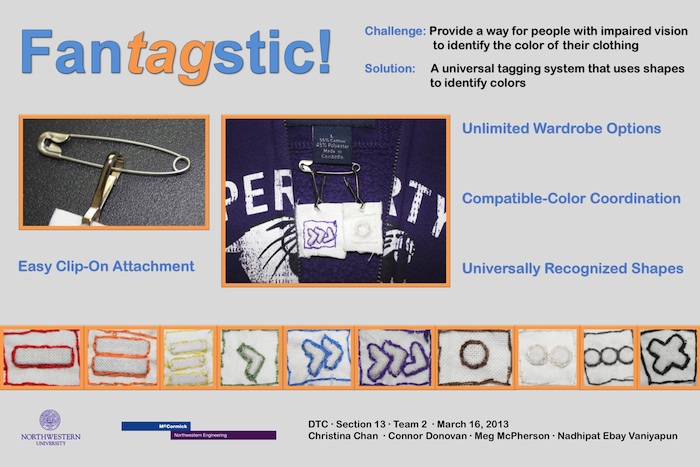

- When you’re doing art, and you have to pick a color, how do you know what it is, you know, if your dog is color blind?

A big thank you to Beth for allowing me to accompany her that morning. Me and the kids at Frances W. Parker School learned a lot that day.