If only

September 11, 2012 • 23 Comments • Posted in Blogroll, guest blog, guide dogs, memoir writing, Uncategorized, writingHava Hegenbarth volunteers as a puppy-raiser for Leader Dogs, and she’s been following my Safe & Sound blog for years. Hava is retired after a career in the diplomatic service, and after reading a recent post here about a Holocaust survivor, she commented that she, too, had survived a genocide — it happened when she’d been assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Rwanda. “People are always telling me I should write a book about this, but I think it would be too painful,” she wrote. “The people I hid did not survive. A shame and sorrow I live with to this day.” Knowing firsthand how therapeutic and cathartic writing can be, I contacted Hava and asked if she’d be willing to write a guest post about her experience. She agreed.

Night comes dark and early to the land of a thousand hills – Rwanda

by Hava Hegenbarth

I was tucked up under my mosquito net and dead asleep when suddenly awakened by a loud explosion. It was the practice for Hutus and Tutsis to throw grenades onto each others homes in the night, but this night it was a much larger noise. My embassy radio crackled to life. It was the ambassador, informing us that the plane carrying the Rwandan president had crashed. It was unknown what this meant or what might be the consequences but that we were to remain in our homes and not attempt to go out. I went back to sleep.

Some time later I was again jarred awake by numerous smaller explosions, mortar and small-arms fire going off all over the town. The embassy radio again squawked to life and we were told to keep away from all windows. I grabbed the radio, a pillow, and took refuge in my hallway. I spent the rest of that night trembling in fear and definitely NOT sleeping.

The gunfire continued on and when dawn finally came there were knocks at my door. I crept cautiously to it and peeked out the window. Africans stood there. I cracked the door and

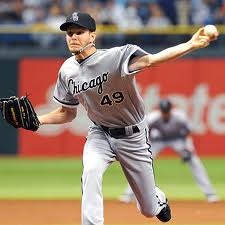

That’s Hava holding Whistle, a puppy she’s raising for Leader Dogs. The big dog in front is Bax, a gift she brought home with her from her last diplomatic post in Mauritius.

whispered “What?” The whispered reply came back. “Madam, hide us!”

Just the week before I’d read the book Schindler’s List. I was amazed at Mr. Schindler’s bravery and wondered how I would react if ever I was in that sort of situation. Now I found myself in that very sort of situation. I took them in.

Four days and three nights we hid together in my house. Outside was hell. There was a high wall surrounding my house, I could not see what was happening but I could hear the horror. There was a pattern to it. There would be screams, then shots, then silence. Over and over again, coming closer and getting louder. I thought that when they got to my house and saw me hiding my refugees, the consequences would be very bad. I just hoped it would be over quickly.

They went past my house. My house was spared. Why? I don’t know. Perhaps at the time they were respecting diplomats’ residences. For whatever reason, we were not invaded.

The ambassador came on the radio and told us to prepare for evacuation. He had negotiated a cease-fire long enough for us to get out. I think they were happy to have us leave so that they could carry on their sinister work without outside eyes seeing it. We were to pack one bag and drive to a predetermined location, there to form up convoys and get out as best we could.

My car was still in customs — I was so new in the country, it had only just arrived in Rwanda. My closest American neighbors offered to pick me up in their car. When they arrived, I dragged my one bag out to the car, followed by my refugees. My friends said, “Hurry up, get in!” I motioned to the refugees. “What about them?”

My friends looked at me in disbelief. “Are you crazy?! No way are they coming!”

I turned to my refugees and feeling the most helpless I have ever in my life told them they could not come with me. They took my hands and pleaded. “Madam, please! You know what will happen to us.”

I knew. I also knew that I would not be allowed to stay with them. The ambassador would never have allowed me to stay nor would he leave until the last American was out of the country. I got into the car. The eyes of the Africans followed the car as it pulled away and out of sight. I still see those eyes. I learned later that they had all been killed.

I’ve relived this many times, wondering if only I had had my own car. If only this. If only that. If only. It all comes out the same. I couldn’t save them.