My Photographic Memory

June 24, 2020 • 30 Comments • Posted in blindnessWhile sheltering in place I’ve been receiving daily updates called “Chicaago History at Home” from the Chicago History Museum. Monday’s message alerted me that legendary photographer and Chicago native Victor Skrebneski had died on April 4 this year. How’d I miss hearing this back then? Oh. Wait. That was the day Mike came home from the hospital, clear of COVID. I was a bit pre-occupied. From the message:

Victor Skrebneski was known for his striking images of models in advertisements and portraits of celebrities, extraordinary editorial photography, as well as numerous breathtaking books and catalogues. He also had a varied and exciting association with the Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum through the years.

Why would a blind woman have a fondness for a photographer? Well, I wasn’t always blind, and the Victor Skrebneski photos I saw when I was a teenager were mesmerizing.

Let me explain. One of my best friends from high school was Matt Klir. We met when I was 16. Seventeen years later, He died of AIDS. He was 33 years old. The COVID 19 pandemic we’re going through now has me thinking back to the horrific AIDS pandemic. And sadly, when I think of AIDS, I think of Matt.

Matt was a year younger than me, we were in the high school band together, and when he signed up for “summer band” after his freshman year we discovered we’d both be bicycling from miles away to attend. We started riding together. A friendship was born.

When neither of us could land a date for a school dance one year we pooled our money and bought Elton John tickets instead. Front row. I wore a polyester red, white and blue halter-topped bridesmaid dress, and Matt wore a powder blue leisure suit. He brought a dozen roses along, and when I handed them to Elton John’s lyricist at the end of the concert, Bernie Taupin said, “Thanks, love.” Matt and I congratulated ourselves all the way home, confident we’d had a wayyyyy better time than anyone at that dumb dance.

Matt’s house became my second home. He and his two sisters were beautiful. His parents were divorced, and the three of them lived with their young vivacious mother in a fancy 1970s sprawling home. Every single time I visited (and that was lots of times!) I’d venture into their dining room and gawk at the huge black and white Victor Skrebneski photos displayed on the walls.

Matt and his two sisters had been childhood models, and when I called Janine and Crystal to ask if either of them still had a copy of the huge b&w photo Victor Skrebneski took of Matt, they knew immediately which one I was talking about.

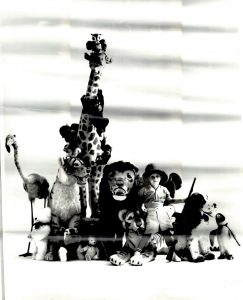

“I remember when Matt was at that shoot,” his older sister Janine wrote in an email. “Victor’s studio was so home-like. Lots of ladies and other people hanging around, comfy couches, along with his impressive photo studio in the main room.” Janine had found the photo of Matt in her basement workshop. “It was rolled up in a box with other old pictures.” She’d had the photo straightened, she scanned it for me, and here it is.

I can no longer take in the photo Victor Skrebneski took of Matt back in the early 1960s for a Marshall Field & Company Christmas ad, but hey, Victor Skrebneski photos are memorable. Matt is there in the lower right hand corner, still a youngster, sporting a safari hat and surrounded by stuffed animals.

Thanks to Victor Skrebneski’s gift and his keen eye, I can still picture young Matt.

What a gift.