Ten years ago my downtown Chicago memoir-writing class got so full that the Department on Aging started a lottery. A retired college professor named Myrna had been attending that class for years, and when her name wasn’t chosen in the lottery, she approached an organization in her own Chicago neighborhood to encourage them to sponsor a writing class there.

Myrna Knepler

Myrna Knepler helped me stretch my wings as a teacher.

Her neighborhood organization said yes, and it’s largely because of Myrna that I found the confidence to lead five memoir-writing classes every week now.

Myrna Knepler died Sunday night, and in her honor, I’m sharing a story about her that dates back to the time I assigned “in-laws” as a writing prompt.

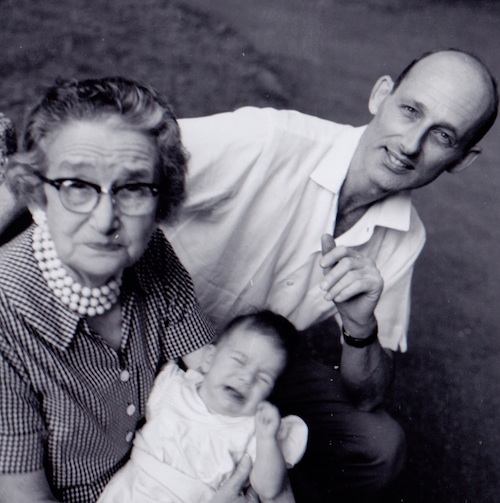

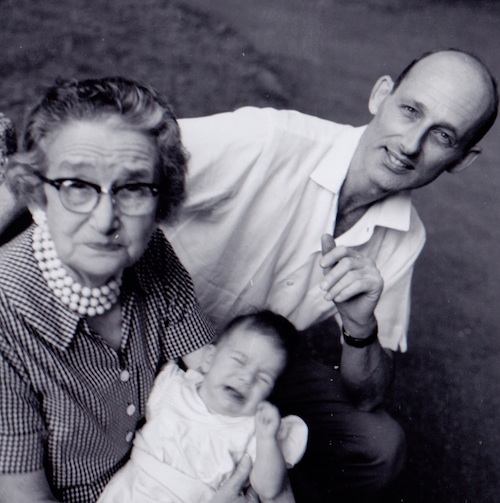

Myrna’s mother-in-law Hedwig is on the left. That’s Henry, Hedwig’s son and Myrna’s husband, on the right. And that’s baby Elizabeth being held by Hedwig. Taken in 1962.

Clever and self-aware, Myrna was one of the very, very, few memoir-writers in my classes who was courageous enough to write about her mother-in law. “Although she had proved both mental and physical sturdiness, she was thin and bent in a way that made her seem fragile and untouchable,” Myrna wrote back in 2012. “Certainly her life experience was beyond anything I knew, in some ways so terrible I was afraid to touch it.”

Myrna’s Husband Henry was only 16 when he said goodbye to his mother and father in Vienna and boarded the Kindertransport (children’s transport), the effort that saved 10,000 Jewish children from the Holocaust. Henry’s father died in the Auschwitz concentration camp. His mother — Hedwig — survived by hiding in an unheated cabin in the Vienna woods, owned by an anti-Nazi family who sheltered her there.

Hedwig would not reunite with Henry, her only child, until he was 24 years old. Myrna would get to know Hedwig Knepler a decade later, after marrying Henry. From her essay:

Moreover, I sensed the tension between her and my husband, her son. I, his new, much younger wife, wanted above all to please him. He loved his mother, but was troubled by what seemed to be her almost obsessive concern for him, a concern more appropriate to the mother of a young boy, than to a balding assistant professor in his late thirties.

Myrna wrote that her conversations with her mother-in-law were awkward until Myrna and Henry had their first daughter, Elizabeth.

Then for the six months between Liz’s birth and Hedwig’s death, talk was easier, focused on our mutual love for and wonder at this new creature, the grandchild she never expected to have.

Hedwig died in 1962, leaving Myrna and Henry to sort through a box of letters Hedwig and Henry had exchanged before and after the war. The letters were written in German (a language Myrna did not know well) and stored in their attic for years. The only time Myrna and her husband Henry opened the cardboard box together, they closed it up right away and put it back on the shelf. The material inside was too painful for Henry to read.

Henry died in 1999, and before his death, when he was too ill to deal with the letters himself, Myrna realized that they were now her responsibility. She unpacked nearly one thousand pages of letters — all typed single-spaced and to the edge of the page — and started sorting them by date to donate to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. In exchange, the museum would translate and make copies for Myrna and her daughters.

The translated letters trickled back to Myrna over a span of six years, during which time Myrna was busy penning her own stories for the memoir-writing classes she was attending — one at the Chicago Cultural Center, and the other in Lincoln Park, sponsored by The Village Chicago. “It would be an understatement to say that the memoir groups have been an important part of her life for the past several years — she’s always loved stories, and being able to write and share her own stories has been so meaningful to her,” Myrna’s youngest daughter Annie wrote in a note to me yesterday. “We are also so grateful to have all of those stories written down.”

Myrna took years pouring over the translated letters forwarded to her from the Holocaust Museum and was finally able to piece together stories of how her mother-in-law helped a brother immigrate safely to Argentina. She read heartbreaking details of her mother-in-law’s attempts to help her mother and aunt, who were already interned. They did not survive. Myrna’s mother-in-law wrote about her own struggles to support herself. About how she starved. How she helped save others. About how, in the end, some of the people she saved ended up helping her.

Thanks to Myrna, the original letters exchanged between Hedwig and Henry are now preserved in a vault outside of Washington, D.C., where scholars can access them.

Myrna spent the last year of her life gathering personal stories Henry wrote for his children. Working with her daughter Annie, Myrna shaped them into a memoir. Leaving Vienna, edited by Myrna and Annie Knepler, will be published by Golden Alley Press later this year.

So here’s to Myrna, A remarkable woman who taught me — and continues to teach us all — so much.