Mondays with Mike: Gute nacht, mein freund

November 19, 2018 • 20 Comments • Posted in Mike Knezovich, Mondays with Mike

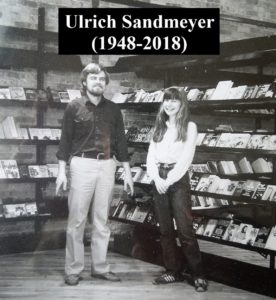

That’s Ulrich and Ellen Sandmeyer, a few years back. If you’re on Facebook, click the image to read a beautiful tribute at the Sandmeyer’s Bookstore page.

The spring of 2003 I was without a job—the weekly newspaper I worked for in Champaign-Urbana had closed its doors at the end of 2002. I hung around the office a couple months to take care of the nasty details.

Our son Gus had moved to a facility for the developmentally disabled in Wisconsin a few months earlier.

I was aimless.

Then, Beth’s first book, “Long Time, No See,” was published in April. It was what I can see now as a demarcation in Beth’s life, and in our lives—one of those many lines in a good life that defines “then” and “now.” Suddenly everything was different. A vacuum presented opportunity.

We each grew up in the suburbs. But neither of us had ever lived in Chicago—the city that defined what a city is for the two of us. If not the spring of 2003, then when?

Back when Beth was at Braille Jail (her nickname for the state rehabilitation facility for newly visually impaired people in the near west side of Chicago) her sister and brother-in-law would occasionally spring her for a meal in the nearby Printers Row neighborhood. Beth had fond memories of those bits of relief from living in the blind version of Cuckoo’s Nest.

That was a start for our finding a new home. I did some online research and we made some visits and eventually leased a place a couple blocks from the real Printers Row. That real Printers Row being one block—maybe two if you’re generous—between Ida B. Wells Drive, a major thoroughfare, and the old Dearborn Station, where Dearborn Street ends. Dearborn Station used to be a bustling train depot, but it now houses yoga studios, medical offices, a Montessori school and the like.

Our neighborhood is so named because most of the buildings on our street were originally used by printing and publishing businesses, or those that supported the logistics of those endeavors. (Also, Elliot Ness once had an office in our condo building, but I digress.)

Back in the day, printers relied on natural light to check their work, so the windows in neighborhood buildings are tall and wide. The ceilings are high, too, to accommodate printing presses and other equipment. The neighborhood went the wrong way for a long time, and most of the lovely old buildings were marked for demolition in the 70s and 80s. Thanks to some stubborn preservationists, the visionary architect Harry Weese (D.C. friends, you have him to thank for the design of your subway stations), and pioneering folks who were willing to homestead in Printers Row, the neighborhood was not lost, but found.

Two of those homesteaders were Ulrich and Ellen Sandmeyer, who opened their bookstore long before Printers Row was a sure bet. I first met Ulrich when I was up from Urbana doing a scouting trip. I stopped in to see if Beth might make a promotional appearance for her book there.

“Nein” was the answer. OK, Ulrich didn’t say it in German, but it was firm. Ulrich Sandmeyer hailed from Germany, spoke impeccable English, but you know, once German, always German. He explained that the store is so small it doesn’t well accommodate such events.

But Beth charmed Ulrich (or did he charm her?), who teased her for her unabashed self-promotion. Ellen—who maintains the shelves and window displays in ways that are both artistic and sales-savvy—put “Long Time, No See” in the front window, trumpeting a local author. This, even though Beth had been local for, oh, a couple months. Ulrich also, as they say in the book business, hand-sold a ton of Beth’s books. The German guy was a damn good salesman.

The Sandmeyers, as much as anyone or anything, made Chicago feel like home.

That was, as Humphrey Bogart would say, the start of a beautiful friendship. Sandmeyer’s Bookstore was and is an anchor—the anchor—of what I, totally biased, think is the best neighborhood in Chicago. And the Sandmeyers became the most wonderful kind of friends that one can make as adults. By that, I mean they already had full lives when we met them, as did we. But somehow, they and we found just enough room for one another.

Sandmeyer’s Bookstore is a polished little gem—every warm, wonderful thing about Ulrich and Ellen courses through it. The wooden floors creak, the radiators clank, the selection is beautifully and intelligently curated with purpose, and there are always witty little novelties at the checkout counter—book lovers’ versions of the candy rack enticing an impulse buy. (My personal favorite was a GW Bush end-of-term countdown clock/keychain.)

Ulrich’s wry sense of humor always astounded me. First, because humor is one of the most nuanced and difficult things to master for a non-native English speaker, and he had mastered it and then some. Second, because like other non-native Americans, he had an outsider’s viewpoint that never failed to open my eyes. I was just another fish in the tank.

He and Beth developed a rich relationship—he came to call the now-closed Hackney’s, our old watering hole—“Beth’s office.” We’d stop by the store just to catch up, talk politics, and have a laugh. We’d run into him outside the store, when he was out taking a smoke break. Like the friendly and crusty beat cop, Ulrich was a comforting, reliable presence to us, and to the whole neighborhood.

Thank you for following along as I get used to using the term “was” when it comes to Ulrich. He died last Friday. I would say “after a long illness.” But, again, humor me: he died of cancer, fucking cancer, goddamn fucking cancer.

I miss him.

I know the drill. I’ll always miss him. The neighborhood will always miss him.

And like the other remarkable people that I’ve been privileged to know, he’ll never really be gone. The last time I saw him was before Amazon announced what cities it would be fleecing for the opportunity to let the company roost. Amazon, let it be said, has not been good for independent bookstores. One of the Sandmeyer’s employees told us the story of how someone once browsed the aisles, picked up a book, and asked, “Do you know how much this costs on Amazon?”

She was astonished.

Ulrich was dispassionate about such things. Or, I should say, he never seemed to take them personally.

I can imagine our talk about Amazon’s decision. I’d get all uppity about it and say good riddance to something we never had.

And I can hear him laughing at me.